At first glance, it looks simply like a time-worn statue of Jesus. The paint is faded, and the arms are broken off.

But with eyes inspired by the principles of Visio Divina, the carved wooden statue at the University of Michigan Museum of Art, called Standing Christ, becomes an artifact of rich spiritual significance, full of mystery and symbolism.

Visio Divina, or “sacred seeing,” has a way of doing that, revealing through the “eyes of the heart” what is hidden, bringing it into the light.

Visio Divina is a prayer process through which a person gains spiritual insight by meditating upon a work of sacred art. Practicing its steps during Lent, by “beholding” images of Christ’s passion or resurrection in contemplative prayer, is a much-recommended way to prepare for a moving Holy Week experience.

A Lenten and Easter season could be even more profound by making a Visio Divina pilgrimage to a church, shrine or art museum, to encounter the spiritual art object firsthand.

Invisible Made Real

Since becoming rector of the Cathedral of the Most Blessed Sacrament in 2015, Father J.J. Mech has initiated programs and pilgrimages that have transformed the cathedral into a center for celebrating culture and the arts. Studying architecture and fine art has always been a “passion” for Father Mech, and Visio Divina has long been a part of his prayer life.

Father suggests that readers give the prayer method a chance, regardless of their prior interest in the arts.

“Visio Divina is not only an ancient form of meditation, but it is an often underutilized one,” Father Mech explains. “Praying with the visible makes the invisible presence of God manifest in a tangible way. It allows an intimate encounter with the love of God.”

There is no better time than during the 40 days of Lent to try Visio Divina, he says. Father Mech proposes “challenging yourself this year to go beyond the usual practice of ‘giving up’ something.” Insights gained by stilling the heart and mind before an image of Christ’s Passion “will allow you to ‘strip away the unnecessary’ and take better stock of your spiritual life—and to grow in it.”

Father Mech points to a painting below from the Detroit Institute of the Arts, Crucifixion by Maerten van Heemskerck, as a sample starting point.

“Before moving to the figure of Jesus,” he suggests, “first focus your gaze upon the pure exhaustion of the Virgin. By identifying your own emotions as you view her pain, you will connect almost immediately to what the Lord has done for you on the cross.”

“How to”

Katie Weiss is another advocate of sacred seeing. Her outreach Behold Visio Divina sponsors workshops on the contemplative prayer method around the country and has produced books and a video series on the practice.

Weiss offers meditative steps adapted from Behold’s Lenten retreat format, using Latin terms to highlight Visio Divina’s ancient history:

Steps of Visio Divina

Visio (look): Gaze at the image or object. Place yourself in the scene. Be aware of what strikes you.

Meditatio (meditate): Be attentive to what God is communicating through words, phrases or questions that arise.

Oratio (prayer): Converse with Jesus “in the secret place of the heart.” Depending on the Holy Week image, your prayer may be one of sorrow, adoration or joy.

Contemplatio (contemplation): Rest in God’s presence. What have you learned from this time of divine intimacy?

Actio (action): Ask God how to apply what you received during the remainder of your Lent.

“Our life as Christians is incarnational,” Weiss explains. “Using our entire body, our senses, we can enter more deeply into a relationship with God.”

Just one example: Catholics for centuries have used the physical imagery of the Stations of the Cross to guide interior prayer. Of course, she notes, the foremost physical example is the Incarnation, Christ taking human form.

No Barriers

Expect the Spirit to reveal even more meaning, Father Mech suggests, by meditating before the actual work of art. Father Mech contrasts how a face-to-face encounter with a loved one is simply more personal than meeting via the Internet. The same goes with art, he says.

“When there is no barrier between you and the artist’s intent, the experience is direct, personal and immediate.” And when placing yourself before a spiritual masterwork during a pilgrimage, Father Mech continues, “One is mentally, physically and spiritually more engaged.”

Here are 12 artworks from three nearby art museums to consider as objects of contemplation this Lent and Holy Week. You may want to read their scriptural references first, thereby pairing Lectio Divina (sacred reading) with Visio Divina.

University of Michigan Museum of Art (UMMA)

The University of Michigan’s Museum of Art is one of the nation’s oldest, founded in 1856. Seekers of the spirit will look for the Richard and Rosann Noel Gallery on the first floor. A collection of about 80 European art objects, mostly Christian themed, spans the time periods 1100-1650.

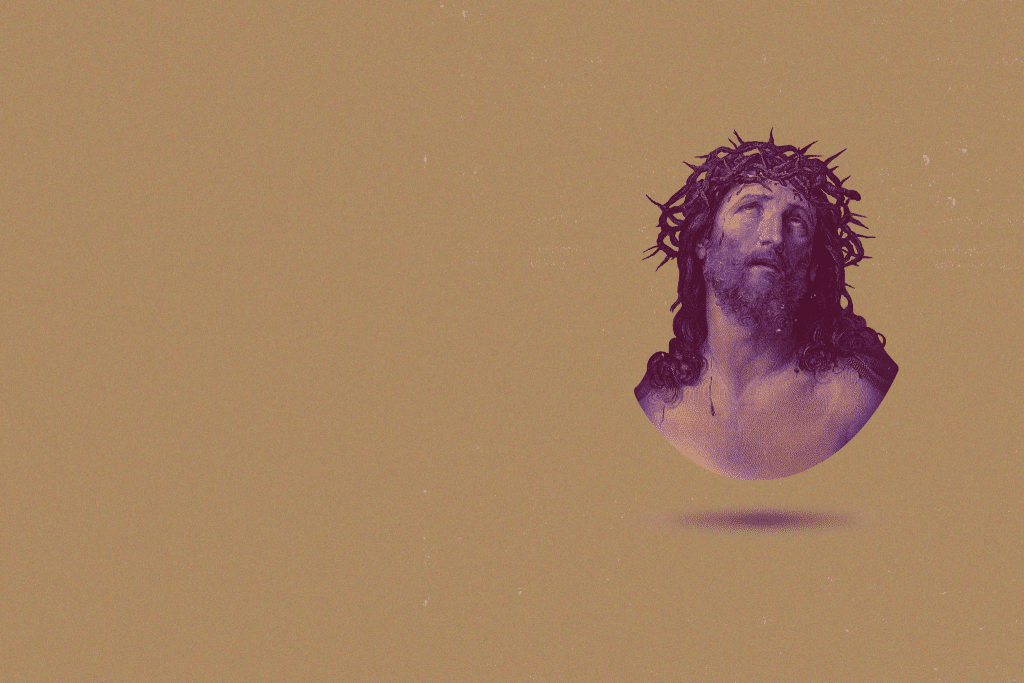

Standing Christ

German, circa 1475

The bared chest of Christ signifies his rising from the tomb. Over the centuries, the stump ends of the wooden arms have become red like blood, like open wounds. Do the broken limbs suggest we are to be the hands of the Risen Christ on earth?

Processional Cross

Italy, circa 1475

Behold the dying Christ is on one side, Christ in triumph on the other. Rare double-sided liturgical cross: either image of Christ would be visible to procession spectators.

Good Thief on the Cross

Germany, circa 1520

The Good Thief, at the moment of passing, sheds his broken body and contemplates the face of Christ or perhaps his coming glory. “Today you will be with me in paradise” (Luke 23:43).

Toledo Museum of Art (TMA)

Toledo—it’s more than just the Mud Hens. In December, I spent a day wandering the Toledo Museum of Art’s many galleries of Medieval, Renaissance, Baroque and Dutch Golden Age masterworks. One word kept coming to mind. “Astounding.”

Seek out the Cloister gallery. Its arches and columns, salvaged from three medieval monasteries, replicate a monastic courtyard. There may be no better place in any museum to practice Visio Divina meditation.

Agony in the Garden

Spanish, circa 1590-1595

The master El Greco depicts Jesus in anguish beneath swirling clouds and a haunting moon. He stretches toward an attending angel offering the cup of betrayal, abuse and torture.

Dead Christ on the Cross

French, 1654

The canvas was a part of the main altarpiece of the mother monastery of the Carthusian religious order. No mourners surround him; the focus is entirely on Christ. “With a loud cry, Jesus breathed his last” (Mark 15:32).

Entombment of Christ

Flemish, circa 1500-1525

Find this wool and silk wonder draped in the Cloister gallery. The Sorrowful Mother, St. John, and St. Mary worship and weep, while Nicodemus and Joseph of Arimathea prepare the brutalized corpse for burial.

Wings of the Wüllersleben Triptych

German, 1503

One panel of the altarpiece shows Jesus in the Garden of Gethsemane surrounded by slumbering disciples: “The spirit is willing, but the flesh is weak” (Mark 14:32-41). Another panel portrays Jesus and his gruesome-faced torturers.

Detroit Museum of Art (DIA)

It makes every short list of top US art museums. The Detroit Museum of Art is recognized especially for its vast collection of European artworks, ranging from the Byzantine (300 a.d.) to the Baroque (1600 a.d.) eras. An interior gallery has limestone columns and barreled ceilings that suggest a Romanesque church.

Betrayal of Christ

Italian, circa 1437-1444

The painting comes from a monastery altarpiece from Tuscany, as do two other panels by Sassetta, Agony in the Garden and Procession to Calvary. All are on brilliant display.

Head of Christ Crowned with Thorns

Italian, early 1630s

Portraying the intensity of Christ’s suffering—“Behold the man!” (John 19:5)—was a hallmark of Baroque period artists. No one does it more vividly than Guido Reni, “the most famous Italian artist of his generation.”

Crucifixion with the Three Marys and Others

English, 1450-1480

How many eyes through the centuries have drawn inspiration from this alabaster prayer aid? The stone carves easily, allowing for high detail.

Crucifixion

Dutch, circa 1530

The focus is on the devastated Blessed Mother, her heart mystically “pierced by a sword” (Luke 2:35). St. John has already taken her into the home of his heart: “Here is your mother” (John 19:27).

Resurrected Christ

Italian, circa 1480

The “Man of Sorrows” (Isaiah 53:3), now in glory, by Sandro Botticelli, the genius of the Sistine Chapel frescoes. “He always strove towards beauty and virtue,” writes a Botticelli biographer.

A Lenten Prayer of Meditation by Father J.J. Mech

Gracious Lord, you are the Divine Artist.

As I enter my prayer, may I center myself not only on your presence outside of me but also deeply within.

As I visually encounter this artwork, may I experience you luring me to a treasure and invitation meant uniquely for me.

Make me aware of the inner stirrings from you, and may I respond from the recesses of my soul.

Let me simply rest in communion with you.

Lord, I want to view all of life through a sacred lens and uncover your messages hidden within creation.

Amen.